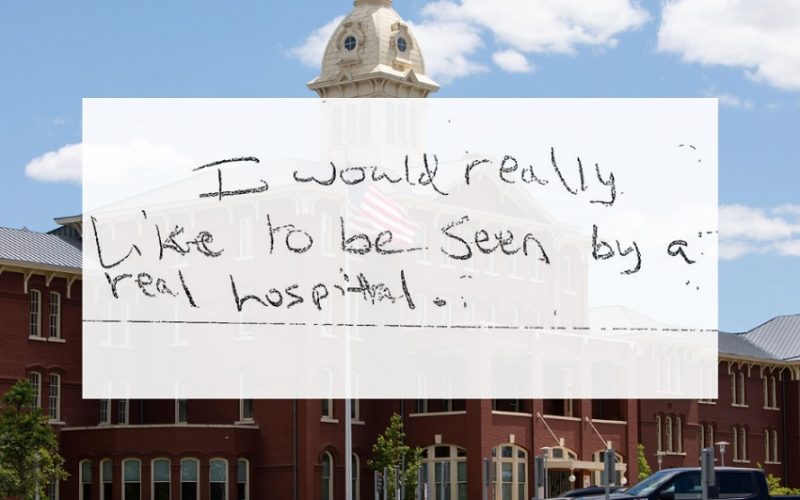

Salem, Oregon — On any given day, the psychiatric units of Salem’s hospitals hum with activity, treating individuals who are in desperate need of care. Yet for many, the treatment is fleeting, the relief temporary, and the return to the streets almost inevitable. This is the stark reality for those caught in the so-called “revolving door” of mental health care in the city—a cycle where patients are admitted for treatment, only to be discharged without sufficient follow-up, left to navigate their recovery without adequate support, and often find themselves back in the same unit weeks or months later.

The problem is not unique to Salem, but it’s felt acutely in this Oregon city, where the shortage of psychiatric resources, combined with overcrowded facilities and insufficient long-term care options, creates a system in which mental health patients struggle to break free from their ongoing crisis.

For many individuals with severe mental health conditions, getting better is a matter of luck. Recovery is too often determined by the availability of space in treatment programs, the timing of a good psychiatric provider, or even just a stroke of fortune—a supportive family member, a timely intervention, or a particularly effective hospital stay.

The cycle begins when patients, often homeless or lacking sufficient social support, are admitted to a psychiatric unit during a crisis. These units are meant to provide acute care, to stabilize patients, and give them a chance to regain some semblance of normalcy. Yet, for most, the period of stability is short-lived. As soon as the immediate danger is addressed—whether it’s through medication, therapy, or physical stabilization—patients are discharged. For some, this could mean a return to a world full of stress, isolation, and a lack of necessary resources, leaving them at high risk of relapse.

“I was in and out of the hospital for years,” says Michael Thompson, a former patient who spent much of his 30s cycling through psychiatric units. “Each time, they’d give me some meds, tell me to follow up with therapy, but there was never enough time to really get better. I just felt like I was sent back out into the world without anything to hold on to.”

Thompson’s story is not unusual. Across Salem, patients like him experience the harsh reality of the mental health care system. Many of these individuals, who suffer from severe psychiatric conditions such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and severe depression, are often discharged without having adequate access to the outpatient services they need. And the results are predictable: patients end up back in the emergency room or psychiatric unit, sometimes in even worse shape than before.

The hospital’s revolving door leaves many questioning how such a system continues to function in a city that has made efforts to address its homelessness and mental health crises. As the population of individuals experiencing mental health crises rises, so too does the strain on resources. Salem’s psychiatric units are frequently at capacity, leading to patients being discharged prematurely or even transferred to other facilities, often miles away, adding additional burdens to those already in crisis.

Dr. Sarah Bennett, a psychiatrist working in the Salem area, explains the fundamental problem: “Mental health care, particularly for individuals who are homeless or without social support, requires consistent, long-term care. But what we’re providing is episodic treatment—here’s your medication, here’s a short-term therapy plan, and then we send you back out with the hope that you’ll stay stable. But the system simply isn’t set up for success.”

The lack of adequate community-based mental health services makes things even worse. There’s a scarcity of available housing for those with severe mental health issues, as well as a shortage of affordable, long-term outpatient programs. As a result, patients discharged from psychiatric units too often find themselves living on the streets, in shelters, or in transient housing, where they have no access to regular medical care or therapy.

In Salem, this lack of resources is particularly pronounced. The city has few long-term mental health facilities, and those that exist are often filled to capacity. Shelters are overwhelmed, and many individuals living with mental health conditions are left to fend for themselves.

For many, the hope of breaking free from the revolving door remains elusive. Without the right care, the right resources, and the right support, many patients feel as though their recovery is a matter of chance, a game of luck in which only a few fortunate individuals manage to find the stability they need.

The need for reform is undeniable. Advocates for mental health care in Salem argue that the city—and the state—must invest more heavily in community-based treatment programs, supported housing, and long-term care options. Without these services, individuals who are discharged from psychiatric units will continue to face the harsh realities of life without adequate support.

“It’s not enough to just put a Band-Aid on the problem,” says Amanda Hughes, an advocate for mental health reform. “We need a system that treats the root causes of mental illness, not just the symptoms. We need resources that help people not just survive, but thrive.”

Until then, those caught in the revolving door of Salem’s psychiatric system will continue to face an uncertain future. For many, recovery will remain a matter of luck—a fleeting hope in an otherwise uncertain world.